A year ago there was a discussion whether a $p$ value is $P(\mathrm{Data}|H_0)$. Some claimed that this is incorrect because $H_0$ is not a random variable and we should instead write $P(\mathrm{Data}; H_0)$ or $P_{H_0}(\mathrm{Data})$.

The controversy arises because, bayesians and frequentists use different definitions of probability. Furthermore in bayesian probability theory, conditional probability is defined axiomatically and the joint probability is derived from it. In frequentist inference it is the other way round.

Here I'm not interested in the frequentist-bayesian quibble. Furthermore, I'm not interested in delving into what is a random event and whether a scientific hypothesis is a random event. Even if $p \neq P(\mathrm{Data}| H_0)$, we can still ask whether it is fruitful to work with the quantity $P(\mathrm{Data}| H_0)$. (Even frequentists are permitted to ask this.) So the question is rather, is it helpful to consider hypothesis as a random variable?

There is lot of fruitful work motivated by the abuse of $p$ values that attempts to derive $P(D|H)$, $P(H|D)$,$P(H)$ or $P(D_\mathrm{replication}|D,H)$ and to show how a particular research strategy alters these quantities. Ultimately this work tends to be inconclusive, because one has to somehow derive $P(H)$. Furthermore, you need to marginalize over $p(D|H)$ for different $H$, which is difficult because $D$ comes from different studies. This is usually done by assuming that the experimental design is similar across studies. Then the contribution of data can be summarized by some quantity such as standardized effect size. Based on the standardized effect size and the prior (and assumptions about the experimental design) one can derive the above-mentioned quantities (e.g. Miller, 2009). One can then simulate what happens to these quantities if some questionable research strategies are applied and finally one can attempt to go in the other direction and ask whether questionable research practices have been used given the quantities that have been previously reported (e.g. Francis, 2013).

The work where the hypothesis is treated as a random variable is useful because it helps us roughly understand how some of the reported findings were/are born. Recently, however I'm becoming more and more skeptical whether the concepts like replication probability, effect size, prior hypothesis probability etc are useful beyond their original task of deconstruction of $p$ values.

Comparing Effect Size across Studies¶

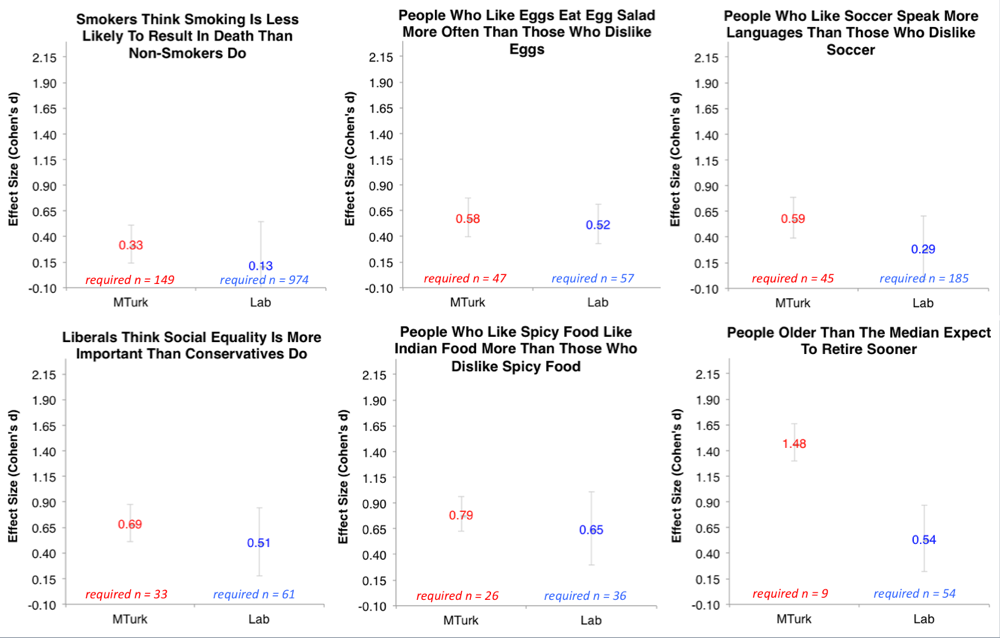

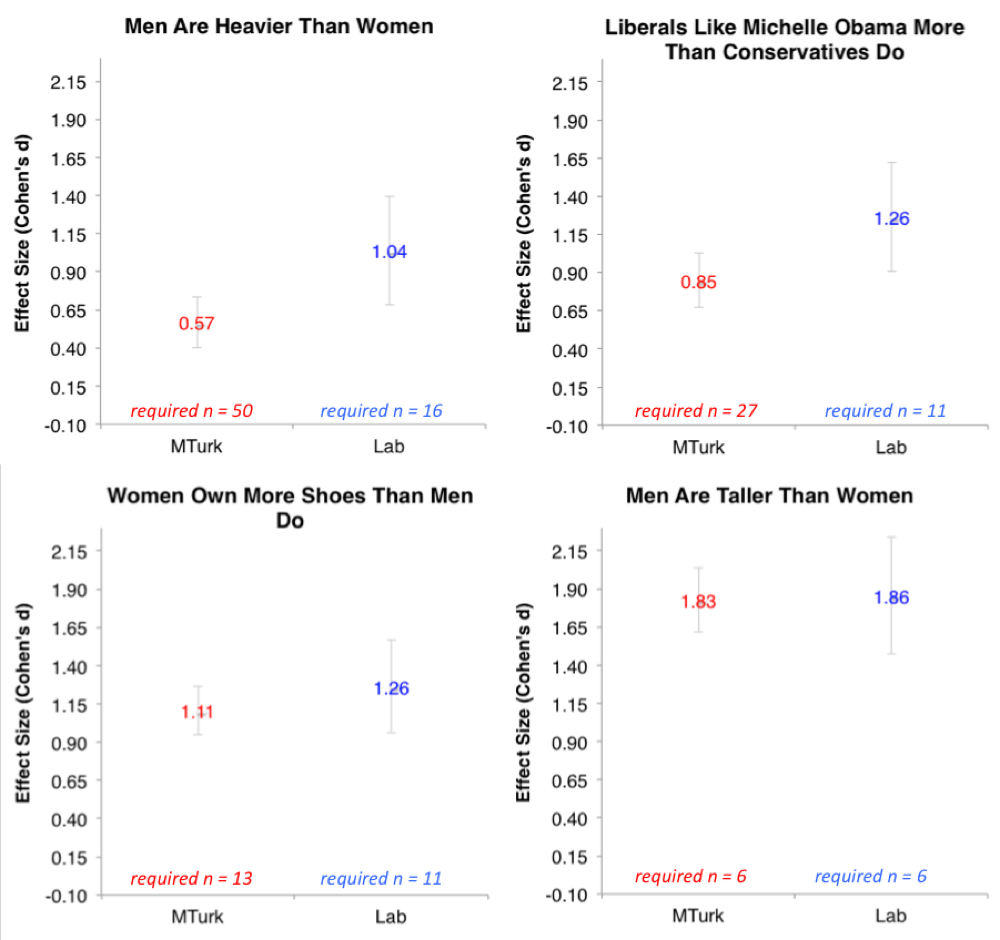

The standardized effect size is used to collapse across studies and this is done across different hypotheses and across different research questions. I see several problems with this. First, I fear this will lead to band-aid answers to problems that require more careful consideration. For instance, Data Colada blog asked whether MTurk studies require larger sample size. They asked subjects ten questions and computed the effect size for some questions that should show reliable and large effects (see below). They compared Mturkers and undergrad students who were tested in the lab. Here are the results.

Data Colada concluded that "the claim that MTurk studies require larger samples is based on intuitions unsupported by evidence." Part of the claim is that the hypothesis is a random variable, this is particularly salient in the above example because the questions are widely varied. It is in contrast with the traditional meta-analysis where the same hypothesis is evaluated across different samples. What I see in the above graphs is that we are mixing apples with oranges. The answer to the question whether Mturk studies require larger samples is that "it depends". We have two populations which differ in many respects. The participants in lab experiments are mostly young female psychology students. The MTurk population is more varied but may not be suitable in some cases (e.g. if we wish to study cognitive performance in people who don't use pc). These differences may be important for some studies and may be irrelevant in other cases. It depends on the subject matter under study and as such considering hypothesis as a random variable and marginalizing over it is not helpful here. I think that the aggregate-study answers to questions like "Do MTurk studies need larger samples sizes?", "What is a strong effect size for memory research?" or "What is the replication probability?" only distract from careful consideration of the specific issues.

There are some less obvious problems that arise when comparing different studies. Additive difference may not be suitable effect size for all studies. As an example consider the following problem. We measure how solution time improves between a first and second attempt at some problem and we compare MTurk subjects with Lab subjects. MTurkers take 40 s and 10 s while Lab subjects take 32 s and 7 s to solve the task. MTurkers show stronger improvement (30 s) than Lab subjects (25 s). So we need larger sample size when we do the experiment in the lab, right?

Consider an MTurker who solves the task in 25 seconds on the first attempt. We expect him to solve the task in $25-30=-5$ s on the second attempt. This doesn't make any sense. We can avoid negative values if we take the difference to be multiplicative. The multiplicative difference is $10/40 = 0.25$. Thus we predict that our fast subject will score $25 \cdot 0.25=6.25$ seconds on the second attempt. This is a reasonable estimate. However what happens with our MTurk vs. Lab comparison if we compare the multiplicative difference? For the lab it's $7/32=0.21$. The Lab subjects now show larger decrease and we need more subjects when we test with MTurk than in the lab. In the case of solution times, the multiplicative model is preferable. However, how should we standardize the multiplicative difference so that we can compare the effect size to other studies where additive difference is more appropriate? Coming back to the example from Data Colada, the use of rating scale in the experiment by data doesn't warrant that the effects are comparable. The processes that generate subject's responses may be differ from question to question and good analysis should take this into account. We are then left with the question, how should we compare parameters of different processes? As the example of additive and multiplicative difference suggests I don't think this is possible nor do I think it is desirable.

More generally, the example illustrates that is unproductive to try to develop measures of $P(D|H)$ in cases where $H$ varies. This is because different $H$ require different models with different parameters and different effect sizes that can't be standardized and compared. Even if we manage to get $P(D|H)$ somehow we still need $P(H)$. This depends on the scope, precision and complexity of the researchers theory, which determines how many and how complex and precise hypotheses can be derived from it. We can write $P(H|T)$ for probability of hypothesis $H$ under theory $T$. A strong theory would allow us to derive lot of precise statements $H_i$ with $P(H_i|T)=1$ or $P(H_i|T)=0$. However, many theories are imprecise so that it is impossible to judge $P(H|T)$ and we can't derive $P(H|D,T)$.

Paradoxically, in the case of pseudo-theories like social-priming or embodied social cognition we can derive $P(H|T)$ for precisely opposite reasons. From these theories one can predict essentially anything so we have uniform prior across all hypotheses $P(H|T)=P(H) \sim 1$ where a hypothesis is any pair of two measurable psychological variables. Furthermore if we constrain our design to simple comparisons we can in all cases use Cohen's $d$ to quantify $P(D|H)$. Then it indeed becomes feasible to compare hypotheses.

The example of social priming highlights that if anything the application of standardized effect sizes is a symptom of a poor research, where

experimental design is strongly governed by the available analysis method so that only few kinds of experimental design (i.e. experimental factor times factor studies) are used and the results become theoretically comparable across studies with widely different questions.

hypotheses are so imprecise and have such a stereotyped structure (A correlates with B, C is larger than D) that they become comparable.

In a healthy science it would not make any sense to consider a hypothesis as a random variable. And of course it would not be necessary. Personally I prefer to build computational models and I try to choose the analysis tool based on the experimental design (which in turn has been chosen with the goal of maximizing ecological validity). I think that for me it should be a straightforward consequence to discard the formulation of a hypothesis as a random variable.